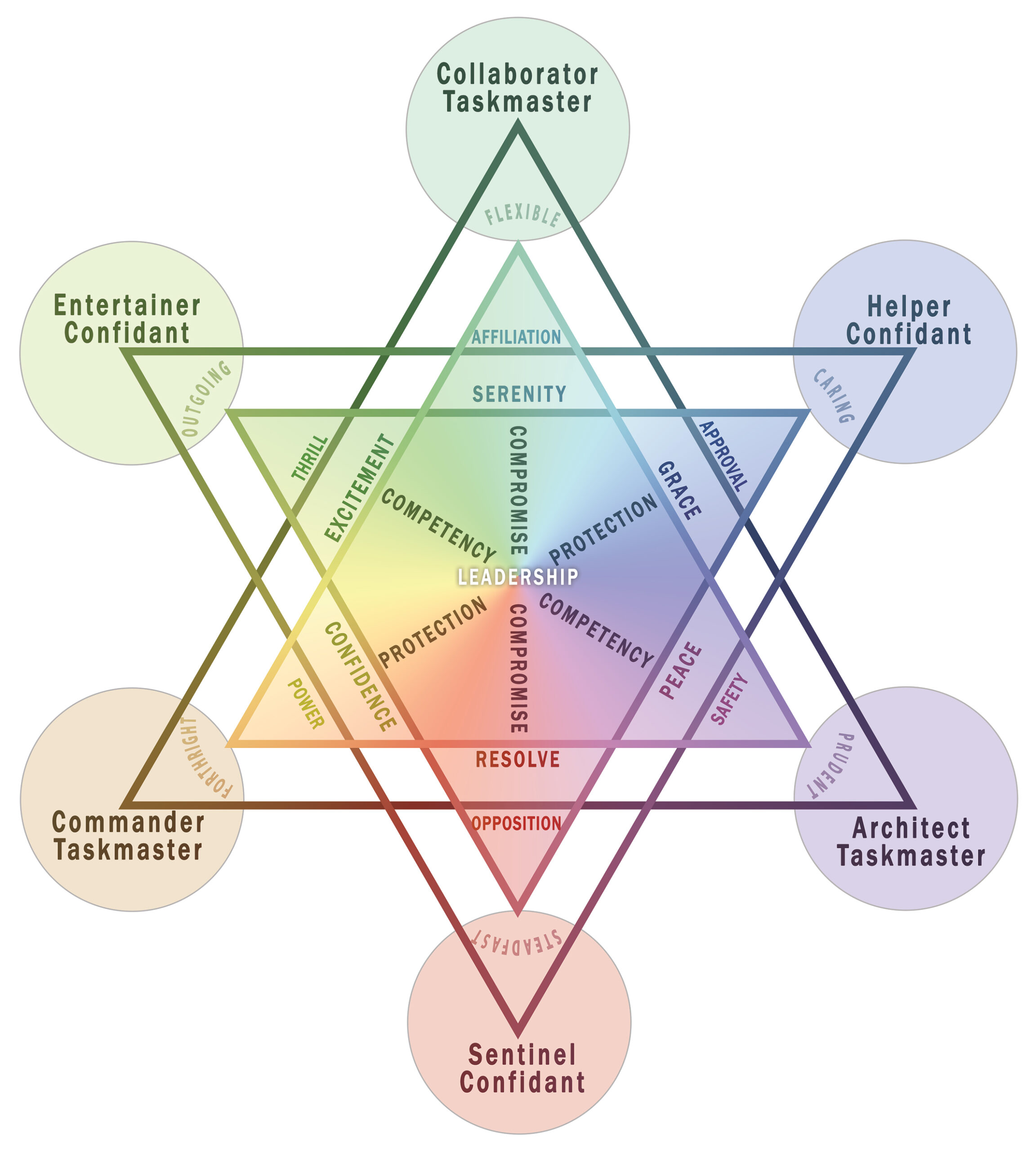

Leadership Virtues

Virtue of Competency: A dynamic blend of the prudent character, shaped by the pressures of sadness and fear, which fosters careful planning and responsible decision-making; paired with the outgoing character, energized by marvel and joy, which brings elements of vigor and enterprise. True competency arises from balancing thoughtful caution with spirited action, enabling a person to navigate challenges skillfully, adapt creatively, and achieve meaningful success through dynamic, dilligent, and strategic work.

Virtue of Compromise: A harmonious integration of two opposing but complementary forces—the steadfast character, driven by the pressures of hate and disgust, which helps uphold a moral high ground that produce a strong conviction and a commitment to the standards one holds; and the flexible character, motivated by the expressions of desire and love, which seeks group harmony and enjoys when others express their wishes. True compromise emerges from blending these elements. It embodies the capacity to navigate challenges with thoughtfulness, balancing perserverence with openess to change. The result is an elegant, skillful approach to life’s complexities—a dynamic interplay between standing firm and flowing with life’s currents.

Virtue of Protection: A balance between the caring character that feels pressured by guilt and shame, which increases the offering of support and understanding due to ethical or religious reasons, and the forthright character that feels empowered by pride and anger, providing guidelines for others on how to behave and express what is wrong and right. True protection comes from merging these two elements, much like a parent who must both nurture and guide their child, being direct and firm while also offering care and support.

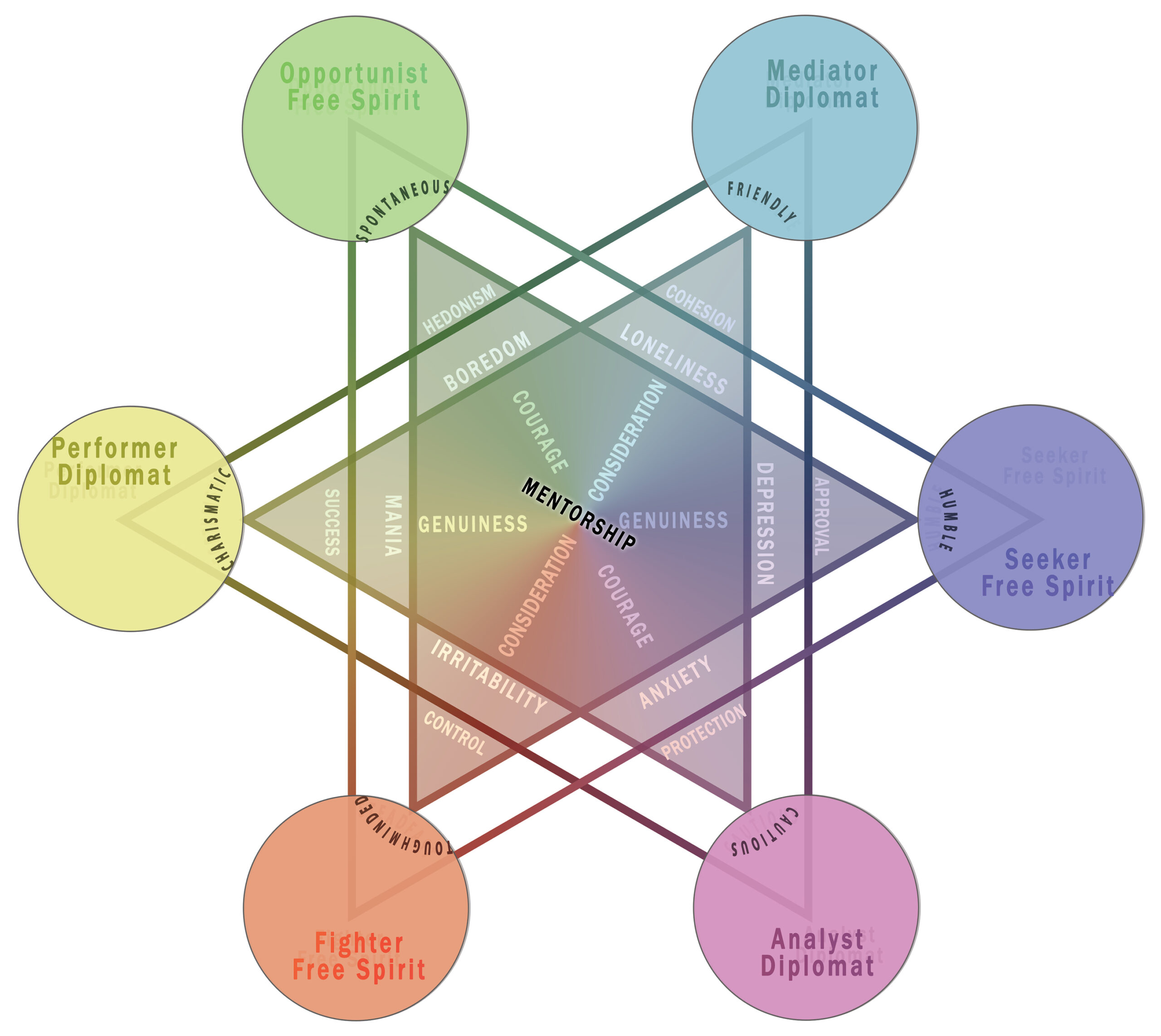

Mentorship Virtues

Virtue of Consideration: A balance between the need for warmth one can offer to another, combining feelings of guilt and love, reflecting their friendly character; Paired with a “toughen up” approach, which involves confronting the person about the negative aspects prompting expressions of anger and hate toward them, embodying a tough-minded character. True consideration is about merging these two elements, where a negative critique is paired with a gentle explanation. This balance fosters growth in true friendship.

Virtue of Genuineness: A balance between the humble character that feels pressured by shame and sadness, which fosters deeper personal self-reflecting insights, and the charismatic character that feels empowered by pride and joy, expressing oneself in one’s positive ideal image without self-doubt. True genuineness comes from merging these two elements, where humility and charisma coexist, creating a self-assuredness to express ones authentic self in the best possible way without a focus on the negative or positive aspect of ones ego. Or better, one’s positive and negative image of oneself aims to capture both in behavior, expressing ones negative traits in a neutral or jokingly was, as well as admitting to one’s positive aspects and not downplaying them.

Virtue of Courage: A balance between the cautious character that feels pressured by fear and disgust, seeking to prevent harm and find stability in the short and long-term future, and the spontaneous character that feels marvel and desire, embracing the wish of trying difficult, novel, and unconventional things. True courage comes from merging these two elements, where both the need to understand the potential harm and the drive for adventure coexist, empowering one to become open to exploring what the world has to offer.

Additional Explanations

This theory is becoming increasingly rigid, and unfortunately, such a rigid personality typology has significant downsides. This is especially problematic given that its foundation stems from an elaborate system explaining how emotions function and what characteristics they produce. These tritypes are not derived from direct human observation but rather emerge as a triangular mathematical outcome based on the characteristics that certain emotions produce—or more precisely, when people properly express specific clusters of emotions.

However, this type of personality construct can be highly productive when teaching people about themselves and others. The theory is a rationalization of what happens when the theory of emotions is split into four personality clusters, determined using triangular geometry. This structure is designed to create a form of balance, where emotions on each side of the triangle generate distinct attributes that differ from the others. Without such a strategic framework, there would be too many possible personality combinations for a person to easily learn. This system is meant to be both practical and intuitive, while also, hopefully, being a fairly accurate reflection of reality.

The rationalization is as follows: People are often unbalanced, meaning their most pronounced trait is typically the result of a certain lack. For example, highly outgoing individuals are often not prudent; they seek thrill and excitement rather than safety and peace. At the same time, closely related characteristics can be set aside if they are too similar to the main trait. Continuing the previous example, an outgoing person could also be fairly charismatic or spontaneous, but this is not necessarily the case. If someone exhibits multiple related traits, it suggests they may have multiple tritypes, making them a more versatile individual.

However, if a person has an imbalance—lacking the traits that counterbalance their dominant characteristics—this suggests an abnormal personality or even pathological tendencies. Such individuals are not versatile but instead highly one-dimensional and predictable in their actions. In contrast, a versatile person is only predictable in the sense that they consistently act with wisdom—that is, they know how to navigate situations in a way that benefits both themselves and others.

Tritypes often hint at imbalance. Most people have one dominant trait, a second that is fairly pronounced, and a third that is weak, hidden, or repressed. However, if all three tritypes are well-balanced, it suggests a very stable and healthy individual—someone who effectively resolves situations using a diverse range of character strategies. The tritype theory allows for the possibility that a person possesses all four tritypes, though some may be less expressed or even repressed. This relates to goal directives and how frequently they are activated. In essence, a person can embody the Confidant, Taskmaster, Diplomat, or Free Spirit, depending on situational demands. The more tritypes a person utilizes, the more adaptable they are.

THE VIRTUE SUPERCLUSTERS:

The primary supercluster is WISDOM, representing the ability to properly assess, respond, and make decisions based on an understanding of their consequences. This wisdom arises from possessing multiple balanced characteristics that align with virtues—the more such virtues a person embodies, the greater their wisdom.

From this wisdom emerge two secondary virtue superclusters: ADAPTATION and RESILIENCE.

Adaptation describes why a person is able to adjust so effectively to different circumstances and environments.

Resilience explains why an individual can maintain stability and quality of response even in difficult situations.

These concepts highlight that even individuals who do not possess an extensive range of virtuous characteristics may still exhibit high levels of adaptation and resilience. However, they may lack a broad variety of behaviors to choose from. Because of this, wisdom is difficult to measure—two tritypes alone may be sufficient to express most, if not all, virtuous behaviors.

Both Leadership and Mentorship—the “super-archetypes”—enable a person to act virtuously in any situation, though their responses will differ according to their goal directives.